Tran Quoc Pagoda: Hanoi’s Timeless Lakeside Sanctuary

Overview and Significance

Essence of Tran Quoc Pagoda

Tran Quoc Pagoda, cradled on a serene peninsula in Hanoi’s West Lake, stands as Vietnam’s oldest temple, its origins shimmering back to 541 CE under the Early Lý Dynasty. Known as the “Guardian of the North,” this Mahayana Buddhist sanctuary weaves ancient spirituality with the tranquil beauty of lotus-draped waters and crimson roofs. Its 1,500-year legacy, crowned by a soaring 11-story Lotus Tower, draws pilgrims, scholars, and wanderers to a sacred haven where Vietnam’s Buddhist soul breathes.

- Defining Trait: Vietnam’s oldest temple, with a 15-century history and a lotus-shaped tower.

- Cultural Role: A beacon of Hanoi’s spiritual resilience and Mahayana Buddhism.

- Global Allure: Hailed by Daily Mail in 2016 as one of the world’s 16 most beautiful temples.

Historical Evolution

Born as Khai Quốc Pagoda (Temple of the Nation’s Opening) under Emperor Lý Nam Đế, the temple’s name echoed the 544 CE founding of Vạn Xuân, an independent Vietnamese state. Was it built to “found the nation”? No, but its title symbolized Lý Nam Đế’s vision of sovereignty, blessing a new era with Buddhist sanctity. Originally perched by the Red River, it moved in 1615 to West Lake’s Kim Ngư Islet to escape erosion, linked by a crimson causeway. Renamed An Quốc (Peaceful Nation) in the 15th century by King Lê Thái Tông, it became Tran Quoc (Guardian of the Nation) under King Lê Hy Tông (1681–1705), a nod to its protective spirit. A 1815 restoration, funded by the Nguyễn Dynasty, preserved its ancient grace, as etched in temple steles.

- Khai Quốc (541 CE): A spiritual emblem of Vạn Xuân’s independence, not a ceremonial founding.

- Relocation (1615): Shifted to West Lake, ensuring survival.

- Name Changes: An Quốc for peace, Tran Quoc for guardianship.

Cultural Impact

Tran Quoc Pagoda is Hanoi’s spiritual heartbeat, its lotus-scented air inspiring poets and artists through centuries. As a Mahayana hub, it has shaped Vietnam’s Buddhist practices, emphasizing compassion and wisdom, with teachings preserved in ancient sutras. Its Vesak festivals unite communities, their lantern-lit processions painting West Lake in golden hues. Beyond Hanoi, it captivates global scholars and travelers, its timeless beauty a testament to Vietnam’s cultural depth.

- Artistic Muse: Depicted in Vietnamese poetry and paintings for its lakeside serenity.

- Buddhist Anchor: A center for Mahayana teachings, influencing national spirituality.

- Community Core: A gathering place for Hanoi’s Buddhists during lunar celebrations.

Signature Legacy

The 11-story Bảo Tháp (Lotus Tower), built in 1998, crowns Tran Quoc, its 66 Amitabha Buddha statues gazing over the lake. A 6th-century legend, carved into temple lore, tells of a monk’s prayers halting a devastating flood, birthing the name “Tran Quoc” as a guardian against calamity. This tale, paired with a Bodhi tree gifted by India in 1959, draws devotees seeking peace, their offerings of lotus flowers a silent prayer for protection.

- Iconic Tower: A 1998 masterpiece, symbolizing enlightenment.

- Flood Legend: A tale of divine protection, etched in local memory.

- Spiritual Draw: A magnet for blessings of peace and prosperity.

Community and Global Reach

Monks chant sutras as families offer incense during Tet, binding Hanoi’s Buddhist community to Tran Quoc’s rhythm. Scholars pore over its ancient steles, while tourists, from Asia to Europe, cross its causeway, enchanted by its serenity. Its 2016 Daily Mail ranking amplified its fame, making it a global pilgrimage site. Amid Hanoi’s bustle, Tran Quoc remains a tranquil oasis, its legacy a bridge between past and present.

- Local Devotion: A daily haven, especially during full-moon rites.

- Scholarly Magnet: Studied for its Buddhist artifacts and inscriptions.

- Global Appeal: Welcomes thousands yearly, seeking spiritual solace.

Architectural Features

Distinctive Design

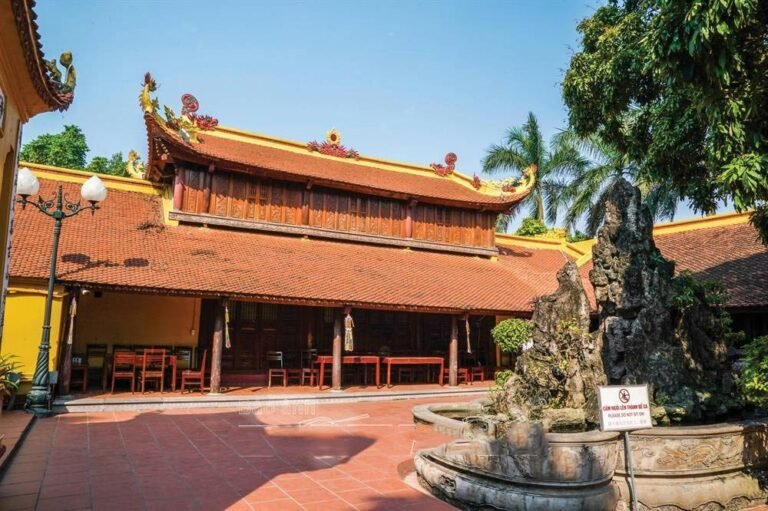

Tran Quoc Pagoda’s architecture dances between ancient Vietnamese elegance and Buddhist symbolism, its compact layout framed by West Lake’s reflective waters. A crimson causeway, like a thread to the divine, links the mainland to a sanctuary of curved roofs and open courtyards. Rooted in Lý Dynasty aesthetics, its design blends 11th-century minimalism with later flourishes, creating a timeless harmony that feels both regal and serene.

- Layout: A central prayer hall, side corridors, rear garden, and Lotus Tower.

- Style: Lý-era curves with Trần-era simplicity, softened by lake views.

- Setting: West Lake’s lotus ponds amplify its spiritual grace.

Signature Structures

The Điện Phật (prayer hall) houses a gilded Shakyamuni Buddha, its serene gaze lit by oil lamps. The 15-meter Lotus Tower, with its 11 tiers and 66 Amitabha statues, rises as a beacon of enlightenment, its white walls and red eaves catching dawn’s glow. The Ancestral Hall, tucked behind, honors past abbots with carved altars, while the causeway, fringed with frangipani, welcomes all to sacred ground.

- Prayer Hall: A compact sanctuary with a golden Buddha and ancient beams.

- Lotus Tower: A 1998 icon, each tier a step toward nirvana.

- Causeway: A 100-meter crimson path, blending earth and spirit.

Artisanal Mastery

Crafted from rosewood, laterite, and clay tiles, Tran Quoc showcases Vietnam’s ancient artistry. The prayer hall’s lotus-carved beams, joined without nails, reflect Lý-era skill, while the Lotus Tower’s hand-sculpted statues reveal modern devotion. The golden lacquer on the Shakyamuni Buddha, reapplied during restorations, gleams with centuries-old techniques, as noted in temple records. Every detail, from roof tiles to statue niches, breathes craftsmanship.

- Materials: Rosewood beams, laterite foundations, clay roofs.

- Techniques: Nail-free joinery, hand-carved reliefs, and lacquerwork.

- Statuary: Over 20 gilded figures, including a 9th-century Bodhisattva.

Hidden Architectural Gems

Beyond the tower, subtle treasures await. A 4th-century stele in the rear garden, inscribed with Sanskrit prayers, whispers of Vietnam’s Buddhist dawn. Faded 18th-century murals along side corridors depict the Buddha’s life in earthy tones, their stories half-lost to time. A modest bell tower cradles a 1815 bronze bell, its chimes rippling across the lake during ceremonies.

- Ancient Stele: A 4th-century relic, etched with early Buddhist verses.

- Murals: 18th-century Jataka tales, fading yet poignant.

- Bell Tower: A bronze bell, rung for peace since 1815.

Preservation and Evolution

Guarding Tran Quoc against humidity and urban sprawl is a quiet devotion. The 1815 Nguyễn Dynasty restoration fortified its foundations with laterite, while the 1998 Lotus Tower added modern splendor without breaking the pagoda’s harmony. Monks and artisans now use natural resins to shield wooden beams from termites, as documented by Hanoi’s heritage board, ensuring this sanctuary endures for centuries more.

- Challenges: Humidity, termites, and Hanoi’s urban growth.

- Restorations: Major in 1815, with ongoing care.

- Modern Efforts: Eco-friendly resins and community upkeep.

Rituals and Practices

Sacred Daily Rites

Dawn breaks with monks chanting the Heart Sutra, their voices weaving through sandalwood incense in Tran Quoc’s prayer hall. Devotees offer lotus flowers and rice to the Shakyamuni Buddha, a gentle act of merit-making. At dusk, candlelit processions circle the Lotus Tower, their golden flickers dancing on West Lake, a ritual as old as the pagoda itself.

- Morning Chants: Sutras at 5 AM, open to all.

- Offerings: Lotus, rice, and incense for purity.

- Evening Walks: Candlelit circles around the tower.

Unique Spiritual Practices

Full-moon ceremonies, held on the 15th lunar day, fill Tran Quoc with the Amitabha Sutra’s cadence, honoring ancestors. Devotees inscribe prayers on lotus-shaped paper, burned in a bronze urn to carry wishes skyward. Monks perform water-blessing rites, sprinkling lake water for purification, a nod to the pagoda’s flood-quelling legend.

- Full-Moon Rites: Chanting and prayer-burning, drawing hundreds.

- Lotus Prayers: Wishes sent heavenward in flames.

- Water Blessings: Lakeside cleansing, tied to ancient lore.

Vibrant Festival Traditions

Vesak, the Buddha’s birthday, transforms Tran Quoc with lotus lanterns and joyous processions, rice porridge shared freely. Tet (Lunar New Year) brings peach blossom offerings and the 1815 bell’s resonant chimes, ushering in prosperity. These festivals blend Mahayana reverence with Vietnamese warmth, uniting monks and laity in celebration.

- Vesak: Lanterns and communal meals under starlight.

- Tet: Blossoms and bell-ringing for fortune.

- Community Spirit: Monks lead, locals organize festivities.

Visitor Engagement

Travelers can light incense, join blessings where monks tie saffron threads for protection, or meditate weekly in the banyan-shaded garden. Inscribing lotus prayers offers a quiet connection to Tran Quoc’s spirit, guided by resident monks. These acts, simple yet profound, invite all to share in the pagoda’s sacred rhythm.

- Incense Offering: Daily, with monk guidance.

- Blessings: Saffron threads, freely given.

- Meditation: Weekly sessions in tranquil shade.

Monastic and Community Roles

Twelve monks, steeped in Mahayana traditions, lead Tran Quoc’s rites and mentor Hanoi’s Buddhist youth. Local families sweep the causeway and tend lotus ponds, a generations-old devotion. Cultural events, like Tet calligraphy workshops, deepen community ties, making Tran Quoc a living bridge between faith and art.

- Monks’ Duties: Chanting, teaching, and outreach.

- Lay Volunteers: Families maintain the grounds.

- Cultural Events: Calligraphy and Buddhist talks, open to all.

Visitor Information

Navigating to Tran Quoc Pagoda

Tran Quoc Pagoda rests along Thanh Niên Road, separating West Lake and Trúc Bạch Lake in Hanoi’s Tây Hồ District. From the Old Quarter, a 10-minute taxi or 20-minute walk via Hàng Bông Street leads to its crimson causeway. The Lotus Tower, rising above lotus ponds, guides the way, with Trấn Vũ Temple nearby as a landmark.

- Route: North from Old Quarter via Hàng Bông, left onto Thanh Niên.

- Landmarks: Trấn Vũ Temple, lakeside cafes.

- Tip: Grab bikes for quick festival-day access.

Address of Tran Quoc Pagoda

Thanh Niên, Yên Phụ, Tây Hồ, Hà Nội, Vietnam

Visiting Hours and Etiquette

Open daily from 7:30 AM to 5:30 PM, Tran Quoc extends hours during Vesak and Tet. Wear modest clothing—covering shoulders and knees—and remove shoes in the prayer hall. Photograph gently, avoiding monks or statues, a quiet nod to Buddhist respect.

- Hours: 7:30 AM–5:30 PM, longer during festivals.

- Dress Code: Modest attire, long pants or skirts.

- Etiquette: No loud talk, no statue-pointing, silence phones.

Accessibility and Safety

A flat causeway welcomes most, but three prayer hall steps may challenge wheelchair users; monks offer aid. The site is safe, though festival crowds invite pickpocket caution. Hanoi’s humidity calls for water and sunscreen, especially on lakeside walks.

- Accessibility: Flat paths, steps at hall; assistance available.

- Safety: Low crime; guard bags during festivals.

- Health: Carry water, wear sunscreen.

Amenities and Surroundings

A small shop sells incense and lotus prayer papers, with restrooms near the garden. Thanh Niên Road’s cafes, like Highlands Coffee, offer phở and iced coffee, while vendors hawk bánh mì. Lotus scents and lapping waves create a sensory haven, softening Hanoi’s urban hum.

- Amenities: Incense shop, restrooms, shaded benches.

- Dining: Cafes and street food nearby.

- Senses: Lotus aromas, lake breezes.

Immersive Visitor Tips

Visit at dawn for monks’ chants in the prayer hall’s golden glow, or dusk for candlelit processions on the lake. Capture the Lotus Tower from the causeway’s end, sans flash, to honor worshippers. Post-visit, stroll Thanh Niên Road for West Lake’s sunset, where fishing boats and lotus ponds weave a tranquil close.

- Best Times: Dawn chants, dusk processions.

- Photography: Tower shots from causeway, no flash.

- Afterward: Lakeside walk for sunset and street food.