Narthang Monastery: The Ancient Printing Heart of Tibet

Narthang Monastery, nestled 15 kilometers west of Shigatse in Tibet’s Tsang province, stands as a silent testament to the enduring legacy of Tibetan Buddhist scholarship and printing artistry. Founded in 1153 by Tumtön Lodrö Drakpa, a disciple of Sharawa Yonten Drak, it rose to prominence as Tibet’s oldest printing center, producing sacred Kangyur and Tengyur scriptures until 1959. Though its grand halls were razed in 1966, leaving only mud-brick foundations and weathered fortress walls, Narthang’s historical resonance and spiritual echoes continue to captivate travelers and researchers. This immersive listing unveils Narthang’s essence, guiding you through its storied past, architectural remnants, sacred traditions, and practical visitor insights, offering a vivid journey into a hidden gem of Tibetan heritage.

The Scholarly Pulse of Narthang

Essence of Narthang Monastery

Narthang Monastery radiates a quiet reverence, its legacy rooted in the Kadampa tradition’s emphasis on scriptural study and monastic discipline. Established in 1153, it later became a Gelugpa branch under Tashilhunpo Monastery, cementing its role as a cultural powerhouse. The monastery’s defining trait—its prodigious printing house, once filled with thousands of engraved wooden blocks—earned it the title “The Library of Tibet.” Despite its current ruins, Narthang’s historical significance as a beacon of Buddhist learning endures, drawing those who seek to trace Tibet’s intellectual and spiritual past.

- Spiritual Core: A Kadampa-turned-Gelugpa monastery, focused on scholarship.

- Iconic Legacy: Tibet’s oldest printing center, producing sacred texts.

- Cultural Role: A hub for Buddhist learning and cultural preservation.

Historical Evolution

Narthang’s story began when Tumtön Lodrö Drakpa, inspired by Atisha’s Kadampa teachings, founded the monastery in Tsang’s fertile plains. By the 14th century, it gained fame as Tibet’s premier printing center, with artisans crafting woodblocks for the Kangyur and Tengyur under royal patronage. In the 17th century, the fifth Dalai Lama and fourth Panchen Lama integrated Narthang into Tashilhunpo’s network, enhancing its printing operations. Tragically, the Cultural Revolution saw its five main halls and chanting hall destroyed in 1966, leaving only foundations and partial walls, though restoration efforts since 1987 have revived three modest halls.

- Founding: Established in 1153 by Tumtön Lodrö Drakpa.

- Printing Era: Became Tibet’s oldest printing center in the 14th century.

- Destruction and Revival: Razed in 1966, partially rebuilt in 1987.

Cultural Impact

Narthang’s printing house was a cultural cornerstone, producing texts that shaped Tibetan Buddhism’s dissemination. From 1730 to 1742, under Abbot Rig-pai-ral-gri and sovereign Pho-lha-nas, it crafted woodblocks for the Narthang canon, a monumental achievement surpassing even the Potala’s efforts. The monastery trained generations of calligraphers, carvers, and printers, preserving Tibet’s literary heritage. Globally, its texts reached Buddhist communities in Mongolia and India, while today, scholars study its legacy through surviving artifacts and historical accounts.

- Printing Legacy: Produced Kangyur and Tengyur, vital Buddhist canons.

- Artisan Training: Fostered skilled printers and calligraphers.

- Global Reach: Texts influenced Buddhist communities worldwide.

Signature Legacy

Narthang’s printing house, once a vast hall filled with rows of wooden blocks, was its crowning achievement. Artisans, inked to their elbows, worked leisurely, sipping butter tea as they printed sacred texts, a scene vividly described by explorer Alexandra David-Neel in 1965. A legendary tale recounts a self-arising stone yak horn, believed to have aided the monastery’s foundation, now housed among its relics. These artifacts, including stone footprints of the eighth abbot, anchor Narthang’s spiritual identity despite its physical loss.

- Printing House: Prodigious woodblock collection, a cultural marvel.

- Self-Arising Relic: Stone yak horn, tied to Narthang’s founding myth.

- Historical Artifacts: Stone footprints and arhat sculptures.

Community and Global Reach

Locals once revered Narthang as a spiritual and educational hub, where monks like the first Dalai Lama studied. Today, nearby villagers visit its rebuilt halls for blessings, though its monastic community is small. The Tibetan diaspora honors Narthang’s legacy through studies of its texts, while international scholars, citing works like Schuman’s Narthang Monastery From the Twelfth Through Fifteenth Centuries, explore its history. Digital archives, such as Mandala Collections, preserve images of its woodblocks, extending its reach.

- Local Ties: Villagers seek blessings at rebuilt halls.

- Diaspora Connection: Honored for its scholarly past.

- Global Scholarship: Studied by historians and archivists.

Architectural Echoes of Narthang

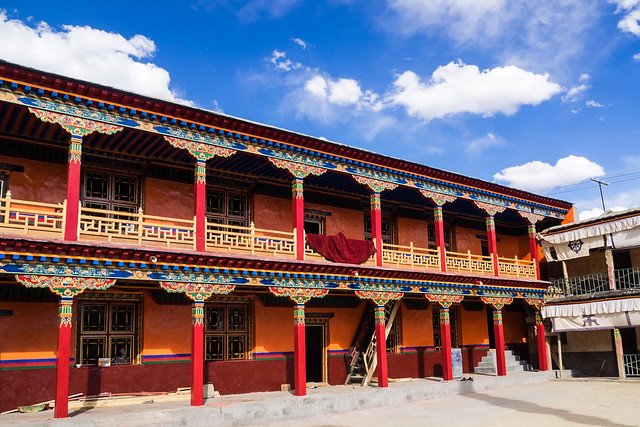

Distinctive Design

Narthang’s original architecture, now largely lost, was a Kadampa masterpiece, blending Tibetan simplicity with fortress-like walls in Mongol style. Spanning several acres, it centered on five main halls and a grand chanting hall, surrounded by monks’ quarters. The printing house, a vast structure filled with wooden block shelves, was its heart, designed for function over ornamentation. Today, only mud-brick foundations and partial high walls remain, evoking a ghostly grandeur against Tsang’s plains.

- Original Layout: Five halls orbiting the printing house.

- Style: Kadampa simplicity with Mongol fortress walls.

- Current State: Foundations and partial walls, a ruinous silhouette.

Signature Structures

The printing house, or barkhang, was Narthang’s core, its shelves once holding thousands of engraved woodblocks. The main assembly hall housed small statues of Denba Tortumba, believed to control lightning, and a mantra stone by the first Dalai Lama. The rebuilt halls, constructed in 1987, contain seven stone sculptures of 16 arhats and the eighth abbot’s footprints, modest echoes of the original grandeur. The chanting hall, once vibrant with debates, is now a memory, its foundations visible among ruins.

- Printing House: Vast hall for woodblock printing.

- Assembly Hall: Housed Denba Tortumba statues and mantra stone.

- Rebuilt Halls: Contain arhat sculptures and footprints.

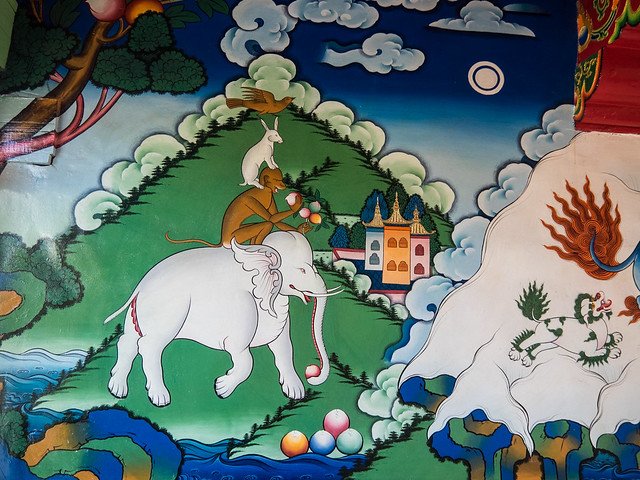

Artisanal Mastery

Narthang’s artisans excelled in woodblock carving, using hardwood to create intricate Kangyur and Tengyur blocks from 1730 to 1742. Calligraphers penned texts with precision, while painters added decorative motifs, possibly influenced by nearby Shalu Monastery’s scholars. The stone arhat sculptures, carved with delicate features, reflect Kadampa craftsmanship. Though 14th-century murals, likely painted by Shalu artisans, adorned the original halls, they were lost in 1966, leaving only historical accounts of their vibrancy.

- Woodblocks: Intricately carved for sacred texts.

- Sculptures: Stone arhats, finely detailed.

- Lost Murals: 14th-century frescoes, now destroyed.

Hidden Architectural Gems

Among Narthang’s ruins, subtle treasures endure. The Mongol-style fortress walls, with their weathered stone, hint at the monastery’s defensive past. Stone-carved mantras, scattered among the foundations, invite quiet reflection. The rebuilt halls house a pair of yak footprints, believed to be self-arising, adding a mystical touch. Visitors can trace the printing house’s outline, imagining artisans at work amidst stacks of paper and ink.

- Fortress Walls: Mongol-style, weathered but evocative.

- Mantras: Stone carvings among ruins.

- Yak Footprints: Mystical relics in rebuilt halls.

Preservation and Evolution

Preserving Narthang’s remnants is challenging due to Tibet’s harsh climate and its ruined state. The 1987 reconstruction, funded by local efforts, rebuilt three small halls, but the original scale remains unrestored. Surviving relics, like the arhat sculptures and 8,800 cultural artifacts, are protected in these halls, though exposure threatens their longevity. Future preservation depends on global support to safeguard Narthang’s historical fragments.

- Reconstruction: Three halls rebuilt in 1987.

- Relic Protection: Arhats and artifacts in modest halls.

- Challenges: Harsh climate and limited funds.

Sacred Rites and Fading Traditions

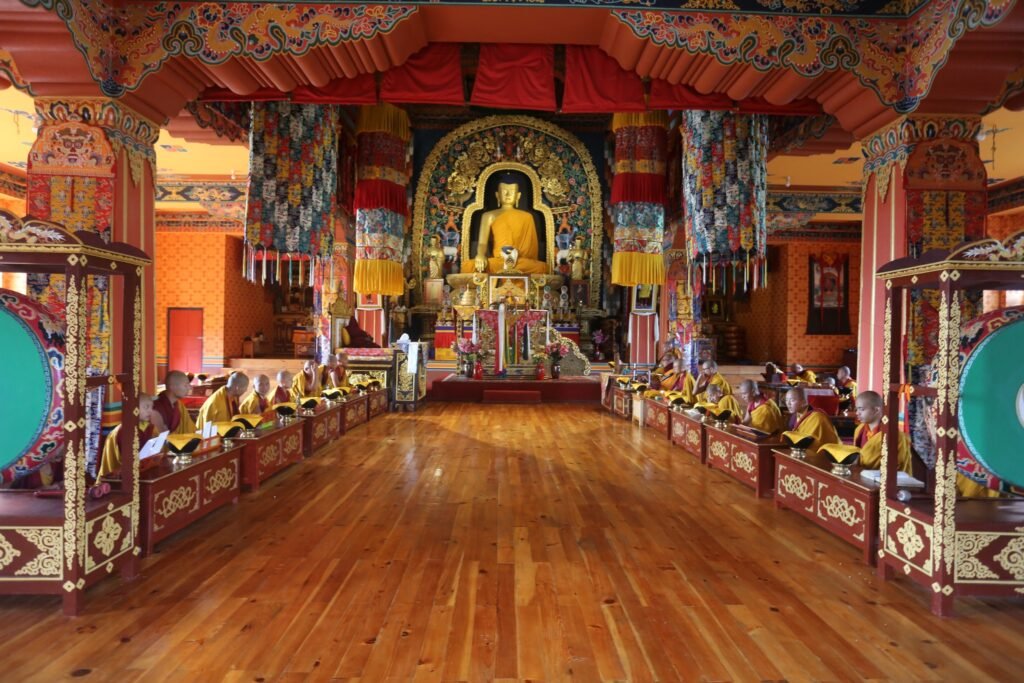

Sacred Daily Rites

In its heyday, Narthang buzzed with morning chants, as monks recited sutras in the chanting hall, their voices mingling with butter lamp smoke. Pilgrims offered khatas (silk scarves) at the Denba Tortumba statues, seeking protection from storms. The printing house hummed with activity, monks cutting paper to size as printers pressed sacred texts. Today, the rebuilt halls host simpler rites, with a few monks maintaining prayers amidst the ruins.

- Historical Rites: Chanting and khata offerings.

- Printing Rituals: Monks printed texts with devotion.

- Current Rites: Modest prayers in rebuilt halls.

Unique Spiritual Practices

Narthang’s monks once performed rituals tied to its printing legacy, consecrating woodblocks with mantras to imbue texts with spiritual power. Pilgrims participated in circumambulation (kora) around the monastery, spinning prayer wheels to accrue merit. The Denba Tortumba statues were focal points for lightning-protection rituals, unique to Narthang. Today, these practices are limited, with monks focusing on basic sutra recitations and relic veneration.

- Woodblock Consecration: Mantras for sacred texts.

- Kora: Circumambulation with prayer wheels.

- Lightning Rituals: Offerings to Denba Tortumba.

Vibrant Festival Traditions

Narthang historically hosted festivals like Losar (Tibetan New Year), where monks and locals gathered for Cham dances and thangka displays. Printing ceremonies, marking the completion of new woodblocks, were festive occasions, with butter tea shared freely. Since the 1966 destruction, festivals have ceased, but nearby villagers occasionally hold small prayer gatherings in the rebuilt halls, echoing past traditions. These modest events preserve Narthang’s communal spirit.

- Losar: Historical Cham dances and celebrations.

- Printing Ceremonies: Festive text completions.

- Current Gatherings: Small prayer events by villagers.

Visitor Engagement

Visitors to Narthang can offer khatas at the arhat sculptures, guided by resident monks, though the community is small. Photography is permitted, capturing the ruins’ stark beauty and rebuilt halls’ relics, but respect for sacred spaces is essential. Joining locals in short prayers offers a glimpse into Narthang’s enduring spirituality. Monks may share stories of the printing house, connecting visitors to its past.

- Offerings: Khatas at arhat sculptures.

- Photography: Allowed, with respect for relics.

- Prayer Participation: Join locals in brief rites.

Monastic and Community Roles

Historically, Narthang’s monks, numbering hundreds, taught scriptures and trained printers, shaping figures like the first Dalai Lama. Today, a handful of monks maintain the rebuilt halls, guiding visitors and preserving relics. Nearby villagers rely on Narthang for blessings during harvests or life events, sustaining a fragile bond. The monastery’s legacy lives through these interactions, despite its diminished scale.

- Historical Role: Educated monks and printers.

- Current Monks: Small group maintains rites.

- Community Ties: Blessings for local events.

Visiting Narthang Monastery

Navigating to Narthang Monastery

Narthang lies 15 kilometers west of Shigatse, along the road to Sakya, in Tibet’s Tsang province. From Lhasa, a 280-km drive via the G318 highway takes 5 hours by bus or private tour vehicle, reaching Shigatse first. From Shigatse’s city center, a 35-minute car or taxi ride covers the 15 km to Narthang, passing Qumig village. The monastery’s ruins, marked by weathered fortress walls, are visible from the road.

- From Lhasa: 5-hour drive to Shigatse on G318.

- From Shigatse: 35-minute car ride, 15 km west.

- Landmarks: Qumig village, fortress walls.

Address of Narthang Monastery

- Location: Qumig Township, Samzhubzê District, Shigatse, Tibet Autonomous Region, China.

- Coordinates: 29.1943° N, 88.7623° E.

- Context: Near Shigatse-Sakya road, rural setting.

Visiting Hours and Etiquette

Narthang’s rebuilt halls are open daily from 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM, though hours may vary due to the small monastic presence; early visits ensure monk guidance. Dress modestly, covering shoulders and knees, and remove hats in prayer areas. Photography is allowed but avoid flash near relics like the arhat sculptures. Respect locals by maintaining silence and not touching artifacts.

- Hours: 9:00 AM–4:00 PM, best in morning.

- Dress Code: Modest clothing, no hats in halls.

- Etiquette: No flash, silence near relics.

Accessibility and Safety

Narthang’s ruins and rebuilt halls are accessible via flat, unpaved paths, but debris may pose challenges for those with mobility issues. Wheelchair users require assistance due to uneven terrain; arrange with tour operators. Shigatse’s 3,800-meter altitude demands acclimatization to avoid sickness; hydrate and rest frequently. The rural setting is safe, but watch for stray dogs and carry cash for local guides.

- Accessibility: Flat paths, some debris.

- Mobility Aids: Limited, arrange assistance.

- Safety: Acclimatize, beware of dogs.

Amenities and Surroundings

Narthang offers minimal amenities, with no restrooms or shops on-site; bring water and snacks. Nearby Qumig village has small teahouses serving momos (dumplings) and butter tea, immersing visitors in rural Tibetan life. The surrounding plains, dotted with barley fields, provide serene spots for reflection. Shigatse’s markets, 15 km away, offer souvenirs and dining options.

- Amenities: None on-site, bring essentials.

- Food: Teahouses in Qumig with momos.

- Surroundings: Barley fields, Shigatse markets nearby.

Immersive Visitor Tips

Visit at sunrise to capture the ruins’ stark beauty against the dawn light, highlighting the fortress walls’ texture. Stand in the printing house’s foundations, imagining artisans at work, and photograph the arhat sculptures from a low angle for dramatic effect. Chat with monks about Narthang’s printing past, enriching your understanding. After exploring, relax in Qumig’s teahouses, savoring butter tea amidst local chatter.