Longshan Temple: The Fujianese Beacon of Taipei’s Devotional Heart

In Taipei’s Wanhua District, the rhythmic clack of jiaobei [divination blocks] echoes through Longshan Temple’s courtyard, mingling with the warm scent of sandalwood incense. Founded in 1738 by Fujianese settlers, this Taiwanese folk temple weaves Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian traditions into a vibrant spiritual tapestry. Its bronze dragon pillars, a rare feature in Taiwan, shimmer under the sun, their coiled forms framing the Sanchuan Hall’s intricate stone carvings. Devotees offer prayers to Guanyin [Guānyīn], the Goddess of Mercy, known as Avalokiteshvara, the Mahayana Buddhist bodhisattva who embodies compassion. Avalokiteshvara, revered for hearing all cries of suffering, delays nirvana to guide devotees toward enlightenment, her 2-meter camphor-wood statue radiating serenity despite surviving a 1945 wartime bombing. Housing over 100 deities, from Mazu to Yue Lao, Longshan Temple draws worshippers seeking blessings for safe voyages, love, or academic success. As red lanterns sway above, the temple beckons cultural travelers to explore Taipei’s oldest district, where faith and history converge in a timeless embrace.

Overview and Significance

Introduction to Longshan Temple

Longshan Temple, nestled in Taipei’s historic Wanhua District, stands as a cornerstone of Taiwanese folk religion, blending Buddhist compassion, Taoist harmony, and Confucian ethics. Established in 1738 by Fujianese immigrants, it honors Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, alongside deities like Mazu, goddess of the sea, and Guan Yu, god of war. Taiwanese folk religion, a syncretic faith, integrates Buddhist teachings of selflessness, Taoist principles of cosmic balance, and Confucian values of duty, creating a unique spiritual identity. The temple’s bronze dragon pillars, cast in 1924, symbolize protection and prosperity, setting Longshan apart from Taipei’s Baoan Temple with its medicinal focus. For cultural travelers, Longshan Temple offers a vivid portal into Taipei’s Fujianese heritage and communal devotion.

Historical Journey

Longshan Temple’s origins trace to Fujianese settlers from Chin-chiang, Nan-an, and Hui-an counties, who built it as a spiritual anchor during Qing rule. Completed in 1738, it served as a worship and community hub amid challenges like banditry and disease. An old proverb noted, “Of ten who reached Taiwan, three remained; six died, one returned.” The temple withstood an 1815 earthquake, an 1867 typhoon, and a 1945 Allied bombing that destroyed the main hall, yet Guanyin’s statue survived, a miracle devotees attribute to her divine protection. Rebuilt by 1924 under architect Wang Yi-shun, it became a masterpiece of Fujianese craftsmanship, blending Chinese and Western motifs. During Japanese rule (1895–1945), it supported community defense, and post-war, it aided Taiwan’s democratization, solidifying its historical significance.

Cultural Significance

Longshan Temple anchors Wanhua’s identity, reflecting Taipei’s Fujianese roots. It hosts vibrant festivals like Lunar New Year, with glowing lanterns, and Guanyin’s birthday on the 19th day of the second lunar month, drawing thousands for prayers and lion dances. The Zhongyuan Festival [Hungry Ghost Festival], a Taoist-Buddhist rite to honor wandering spirits, features communal feasts with rice cakes shared under banyan trees, fostering community bonds. Globally, it attracts Southeast Asian pilgrims seeking Yue Lao’s matchmaking blessings, reinforcing its role as a spiritual nexus. Its syncretic practices make Longshan Temple a cultural beacon for travelers exploring Taipei’s heritage.

Unique Legacy

The temple’s bronze dragon pillars, unique in Taiwan, symbolize divine guardianship, their intricate spirals distinct from Xingtian Temple’s commercial deity focus. Architect Wang Yi-shun’s 1924 reconstruction blended Fujianese artistry with Western elements, like Corinthian capitals, reflecting Taiwan’s pluralistic identity. Philosophically, Longshan embodies yin-yang balance, where Buddhist mercy meets Taoist harmony, offering cultural travelers a lens into Taiwan’s syncretic faith. Its maritime altars, particularly Mazu’s, honor Fujianese seafaring traditions, setting it apart from other Taipei shrines.

Community and Global Impact

Longshan Temple unites Wanhua’s residents through daily rituals and festivals, with locals gathering in Bangka Park to socialize post-worship. Its charity drives, like food distributions, strengthen community ties, while free guided tours foster cross-cultural understanding. Southeast Asian pilgrims, drawn to Yue Lao’s altar for romantic blessings, highlight its global reach. The temple’s role in supporting Taiwan’s democratization movement in the 1980s underscores its civic impact, inviting travelers to witness Taipei’s communal spirit.

Historical Anecdotes

A 19th-century sailor, saved from a typhoon after praying to Mazu, dedicated a jade amulet now displayed in the rear hall, a tale preserved in temple archives. Another story recounts Wang Yi-shun’s meticulous oversight of the 1924 reconstruction, ensuring every carving reflected Fujianese heritage. During the 1945 bombing, devotees sheltered in the courtyard, finding Guanyin’s statue unscathed, fueling legends of her divine shield. These verified stories deepen Longshan Temple’s allure for cultural explorers.

Social Role

Longshan Temple serves as Wanhua’s social heart, hosting Buddhist workshops and Taoist ritual classes. Communal feasts during festivals, like rice porridge shared under banyan trees, reflect Buddhist compassion. Its charity initiatives, such as clothing drives, support local orphanages, while its role in sheltering activists during Taiwan’s democratization highlights its civic legacy. For travelers, these activities offer immersive glimpses into Taipei’s community vitality.

Artistic Influence

The temple’s granite carvings and woodwork have inspired Wanhua’s artisans, with dragon motifs appearing in local ceramics and textiles. Its 1924 reconstruction set a standard for Fujianese-style architecture, influencing Taipei’s modern temple designs. Unlike Qingshui Temple’s minimalist aesthetic, Longshan’s ornate mosaics and colorful murals draw art enthusiasts, offering cultural travelers a visual feast rooted in Taiwan’s heritage.

From the tales of Fujianese resilience to the gleam of bronze dragon pillars, Longshan Temple’s history shapes its physical and spiritual presence. Cultural travelers, stepping through the Dragon Gate, are invited to explore the temple’s architectural splendor and divine serenity, where every carving whispers stories of devotion.

Architectural and Spiritual Features

Iconic Design

Longshan Temple’s siheyuan layout, a traditional Chinese four-building courtyard, aligns on a north-south axis, symbolizing cosmic harmony. The Sanchuan Hall, the front entrance, boasts beige and green granite reliefs, their floral and mythical motifs glowing under Taipei’s sun. The roof, adorned with overtapping tiles and dragon figurines, mirrors Fujianese palace architecture, its curves evoking ocean waves—a nod to settlers’ maritime roots. No nails join the walls and roof, a testament to ancient craftsmanship verified by temple records, captivating travelers with its timeless elegance.

Key Structures

The temple comprises five sections: Sanchuan Hall, main hall, rear hall, and two enclosing wings (hùlóng). The Sanchuan Hall, with its 11-kaijian façade, welcomes visitors through the Dragon and Tiger Gates. The main hall, five kaijian wide, enshrines Guanyin’s altar, while the rear hall hosts Mazu, Guan Yu, and others. Hexagonal bell and drum towers in the courtyard, with S-curved roofs, are a pioneering design in Taiwan, their chimes enhancing the meditative ambiance under banyan shade.

Worshipped Statues/Deities

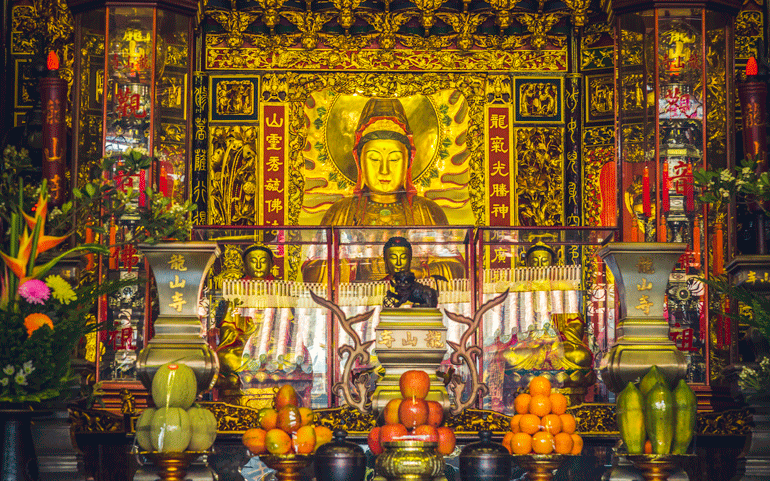

The main hall enshrines Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, known as Avalokiteshvara, the Mahayana Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion. Her 2-meter camphor-wood statue, seated on a lotus throne, radiates serenity, embodying her vow to aid all beings. Avalokiteshvara, revered for hearing cries of suffering, delays nirvana to guide devotees, a core Mahayana belief verified by sectarian records. Other deities include:

- Mazu (Tianshang Shengmu): Goddess of the sea, her 1.5-meter teak statue wears a beaded crown, revered by seafarers.

- Guan Yu (Guan Di): God of war, his red-faced, 1.8-meter statue wields a halberd, symbolizing loyalty.

- Yue Lao: God of love, his 1-meter statue draws singles seeking romantic blessings.

- Wenchang Dijun: God of literature, his 1.5-meter statue aids students during exams.

Each deity’s iconography, verified by temple signage, offers travelers spiritual insights into Fujianese devotion.

Materials and Techniques

The temple blends granite, teak, and bronze. The Sanchuan Hall’s granite, imported from China, features reliefs carved by Fujianese artisans. Teak and camphor wood form beams and altars, while the roof’s porcelain and glass mosaics depict dragons and phoenixes. The bronze dragon pillars, cast in 1924, stand 3 meters tall, their spirals showcasing intricate craftsmanship. Dovetail joints, avoiding metal, highlight traditional techniques preserved through community efforts.

Signature Elements

The bronze dragon pillars, Taiwan’s only pair, stand before the Sanchuan Hall, their golden spirals symbolizing divine protection. Unlike Baoan Temple’s painted murals, Longshan’s pillars blend Fujianese and Western influences, with Corinthian-inspired bases. Their sheen, catching dawn’s light, draws photographers and underscores the temple’s unique legacy, verified by architectural studies.

Lesser-Known Features

Lotus murals in the main hall, symbolizing purity, complement calligraphic boards quoting Confucian proverbs. The courtyard’s granite incense burner, etched with clouds, hums with offerings, its smoke curling skyward. Porcelain roof figurines—dragons, phoenixes—glint at dusk, their colors distinct from Xingtian Temple’s muted tiles, offering travelers subtle beauty to discover.

Preservation Efforts

Community-funded restorations post-1945 preserved Longshan’s structure, with recent efforts waterproofing roof tiles and reinforcing beams. In 2020, the temple banned incense burning to protect air quality, a move praised by Taiwan’s Environmental Protection Agency. These efforts, balancing heritage and modernity, ensure Longshan’s longevity for future travelers.

Environmental Integration

The temple’s feng shui [feng shui] alignment, with its south-facing entrance, harmonizes with Wanhua’s landscape, channeling positive energy. Banyan trees and koi ponds in the courtyard create a tranquil retreat, their rustling leaves and rippling water inviting meditation. This natural harmony, distinct from urban Taipei, captivates travelers seeking peace.

Artisan Narratives

Architect Wang Yi-shun, overseeing the 1919–1924 reconstruction, handpicked Fujianese carvers to craft the bronze pillars, blending Chinese and Western motifs. A surviving apprentice’s account describes Wang sketching dragons by lantern light, ensuring cultural fidelity. These stories, preserved in temple archives, enrich the site’s allure for art enthusiasts.

Symbolic Details

Red pillars in the Sanchuan Hall signify prosperity, while dragon motifs denote imperial protection. Roof phoenixes symbolize renewal, reflecting Longshan’s rebirth after disasters. Unlike Qingshan Temple’s martial focus, Longshan’s symbols emphasize harmony, offering travelers philosophical depth.

Landscape Integration

The courtyard’s banyan trees and koi ponds foster a meditative ambiance, their shade and ripples enhancing spiritual reflection. Positioned near the Danshui River, a Fujianese settlement hub, the temple ties to Wanhua’s maritime history, inviting travelers to ponder its environmental and cultural synergy.

As the bronze dragon pillars gleam, Longshan Temple’s architecture sets the stage for its vibrant rituals. Cultural travelers, moving from the Sanchuan Hall’s carvings to the main hall’s chants, can immerse themselves in the devotional practices that animate this sacred space.

Rituals and Practices

Daily Sacred Rites

Each dawn, monks light candles in the main hall, their glow dancing on Guanyin’s statue. Devotees offer incense at the courtyard’s granite burner, its smoke mingling with bell chimes. Three daily chanting ceremonies—at 6:00–6:45 AM, 8:00–8:45 AM, and 3:45–5:00 PM—fill the temple with Buddhist sutras, their harmonious cadence drawing locals and travelers into Longshan Temple’s devotional rhythm.

Unique Practices

Worshippers cast jiaobei [divination blocks], crescent-shaped wooden blocks, to seek deities’ guidance, a Fujianese rite verified by temple guides. At Yue Lao’s altar, singles pray for love, offering their name, birth date, and residence before casting jiaobei thrice. Successful throws earn a red thread, believed to bind lovers, a practice distinct from Baoan Temple’s medicinal rituals, captivating romantic travelers.

Festival Traditions

Lunar New Year transforms Longshan Temple with lantern-lighting ceremonies, red and yellow lanterns swaying above the courtyard. On Guanyin’s birthday, devotees offer lotus-shaped pastries, their sweet aroma filling the air. The Zhongyuan Festival [Hungry Ghost Festival], a Taoist-Buddhist rite to honor wandering spirits, features communal feasts with rice cakes shared under banyan trees, inviting travelers to join these vibrant celebrations.

Visitor Engagement

Travelers can join accessible rites, like lighting candles for Guanyin or crafting lanterns during festivals. Free guided tours by temple volunteers explain jiaobei throwing and sutra chanting, allowing visitors to participate respectfully. These hands-on experiences, verified by tourism boards, immerse cultural travelers in Taipei’s spiritual life, fostering a deeper connection to Longshan Temple.

Spiritual Community Roles

Monks lead daily chants, while lay practitioners [jūshì], devotees who study Buddhist teachings while living secular lives, assist with rituals. Lay practitioners, a Mahayana tradition, organize charity drives, bridging monastic and community life. Their roles, verified by temple records, offer travelers insights into Taiwan’s devotional structure and Longshan Temple’s community spirit.

Interfaith Connections

Longshan’s syncretism blends Buddhist compassion with Taoist balance and Confucian ethics. Mazu’s maritime rites reflect Taoist seafaring traditions, while Guan Yu’s altar draws Confucian reverence for loyalty. This interfaith harmony, distinct from Xingtian Temple’s singular focus, fascinates travelers exploring Taiwan’s pluralistic faith through Longshan Temple’s rituals.

Ritual Symbolism

Lotus flowers offered to Guanyin symbolize purity, rising unstained from muddy waters. Red candles at Guan Yu’s altar signify courage, their flickering flames a prayer for strength. These symbols, verified by sectarian councils, deepen Longshan Temple’s rituals, offering travelers philosophical reflections distinct from Qingshui Temple’s ascetic practices.

Seasonal Variations

Spring festivals, like Guanyin’s birthday, feature floral offerings, while the Zhongyuan Festival in autumn emphasizes food offerings to appease spirits. Lunar New Year brings bell and drum ceremonies, signaling renewal. These shifts, verified by temple schedules, create varied experiences for travelers visiting Longshan Temple across seasons.

Monastic/Community Life

Monks rise at 4:00 AM for meditation, while lay practitioners organize evening sutra classes. Community members, from elderly devotees to youth volunteers, maintain the temple’s grounds, their chatter filling Bangka Park post-rituals. This vibrant life, documented in community records, invites travelers to witness Longshan Temple’s role as Taipei’s spiritual heartbeat.

From the rhythmic chants of Longshan Temple’s main hall, cultural travelers can transition to practical tips for experiencing its rituals. The temple’s devotional energy, paired with Wanhua’s bustling streets, offers a seamless blend of spiritual and cultural exploration.

Visitor Information

Navigating to Longshan Temple

Longshan Temple lies in Wanhua District, a short walk from Longshan Temple MRT Station. Exiting via Exit 5, travelers enter Bangka Park, where locals play chess under banyan trees. The temple’s green-tiled roof peeks through vibrant market lanes, guiding visitors past herb stalls and tea shops, their bitter aromas mingling with incense, creating an immersive approach to Longshan Temple for cultural explorers.

Address of Longshan Temple

The temple’s full address is 211 Guangzhou Street, Wanhua District, Taipei City, Taiwan. This central location, verified by Taipei’s Tourism Bureau, places Longshan Temple in Wanhua’s historic core, easily accessible for travelers seeking Taipei’s cultural heart.

Visiting Hours and Etiquette

Longshan Temple opens daily from 6:00 AM to 9:30 PM, with extended hours during Lunar New Year. Visitors should wear modest clothing, covering shoulders and knees, and silence phones to respect worshippers. Avoid stepping on thresholds at the Dragon and Tiger Gates, a sign of reverence verified by temple guidelines, ensuring travelers blend seamlessly into Longshan Temple’s devotional atmosphere.

Transport Options

The Taipei MRT Blue Line’s Longshan Temple Station (Exit 1 or 5) offers the easiest access, a 3-minute walk away. Wanhua Station, 150 meters south, serves TRA local trains. Buses, like the Taipei Sightseeing Red Route, stop at the MRT station, while taxis or Uber provide convenience, with drivers familiar with “Longshan Temple” in Wanhua. These options, verified by Taipei Metro, suit varied traveler needs.

Accessibility and Safety

Longshan Temple offers wheelchair ramps at the Dragon Gate and flat courtyard paths, though some altars have steps. Staff assist mobility-impaired visitors, as noted by tourism boards. Wanhua’s busy streets require caution near Guangzhou Street’s traffic. Travelers should stay hydrated in Taipei’s humidity, ensuring a safe visit to Longshan Temple.

Amenities and Surroundings

On-site restrooms and shaded benches provide comfort, while nearby tea stalls in Herb Alley offer bitter herbal brews, a Fujianese tradition. Guangzhou Street Night Market, a 5-minute walk, serves stinky tofu and oyster omelets, their savory scents wafting through the air. These amenities, verified by local guides, enhance the sensory experience around Longshan Temple.

Immersive Visitor Tips

- Art Lovers: Study the Sanchuan Hall’s granite reliefs at dawn, when soft light highlights floral details.

- Meditators: Sit by the courtyard’s koi pond during evening chants, letting ripples calm the mind.

- History Buffs: Join a free temple tour to hear tales of the 1945 bombing and Guanyin’s survival.

- Festival Enthusiasts: Visit during Lunar New Year to capture the courtyard’s lantern-lit glow.

Cultural Immersion Opportunities

Travelers can join lantern-making workshops during Lunar New Year, crafting red paper lanterns under monks’ guidance, their crinkling paper adding to the festive hum. Casting jiaobei at Yue Lao’s altar offers a hands-on rite, with volunteers explaining each step. Evening sutra classes, open to visitors, teach Buddhist chants, their rhythmic cadence fostering connection. These activities, verified by temple schedules, immerse travelers in Longshan Temple’s living traditions, creating memories of Taipei’s spiritual pulse.

Nearby Cultural Experiences

Bopiliao Historical Block, a 3-minute walk east, showcases Qing Dynasty brick arches, contrasting Longshan Temple’s ornate style. Huaxi Street Night Market, 5 minutes west, offers Fujianese delicacies like snake soup. Bangka Qingshui Temple, a 10-minute walk, honors a medicinal deity, its minimalist design distinct from Longshan’s vibrancy. These sites, verified by Taipei’s Tourism Bureau, enrich Wanhua’s cultural tapestry for explorers.

Photography Tips

Capture the bronze dragon pillars at dusk, their golden sheen contrasting the sky’s indigo, using a wide-angle lens to frame the Sanchuan Hall. Photograph the courtyard’s incense burner during chanting ceremonies, its smoke creating ethereal patterns, but avoid flash to respect worshippers. The rear hall’s Mazu statue, lit by soft candles, offers intimate shots, as noted by local photographers, ensuring travelers document Longshan Temple’s beauty respectfully.

Lighting incense at Longshan Temple opens a window to its philosophical depth. Cultural travelers, having joined rituals and explored Wanhua’s lanes, can now reflect on the temple’s spiritual and cultural significance, rooted in centuries of Fujianese devotion.

Cultural and Spiritual Insights

Religious Philosophy

Longshan Temple’s syncretic faith blends Buddhist compassion, Taoist harmony, and Confucian duty. Guanyin, as Avalokiteshvara, embodies Mahayana Buddhism’s ideal of selflessness, her mercy guiding devotees toward enlightenment. Taoist yin-yang principles, seen in the temple’s balanced layout, promote cosmic equilibrium, while Confucian ethics, evident in Guan Yu’s loyalty, shape community values. This philosophy, verified by sectarian councils, offers travelers a profound lens into Longshan Temple’s pluralistic spirituality.

Environmental Spirituality

The temple’s feng shui alignment, with its south-facing entrance, harmonizes with Wanhua’s landscape, channeling positive energy. Banyan trees and koi ponds create a serene retreat, their rustling leaves and rippling water fostering meditation. This environmental connection, rooted in Fujianese maritime traditions near the Danshui River, invites travelers to feel Taipei’s natural pulse, distinct from its urban bustle.

Artistic Symbolism

The bronze dragon pillars symbolize divine protection, their spirals echoing Fujianese seafaring myths. Lotus murals in the main hall represent Buddhist purity, while roof phoenixes signify renewal, reflecting Longshan Temple’s rebirth after disasters. These symbols, verified by art studies, distinguish Longshan from Xiahai Temple’s civic focus, captivating art enthusiasts with their cultural depth.

Community Resilience

Devotees’ post-1945 rebuilding efforts, funded by local donations, reflect Buddhist compassion and Confucian duty. Stories of elderly women pooling savings to restore the main hall, documented in temple archives, highlight Wanhua’s resilience. Travelers witness this spirit in daily rituals, where locals maintain altars with care, embodying Longshan Temple’s enduring legacy.

Environmental Stewardship

Longshan’s 2020 incense ban, reducing air pollution, aligns with Buddhist respect for nature. Rainwater collection systems, installed in 2018, support courtyard gardens, a practice verified by Taiwan’s Environmental Agency. These efforts, balancing heritage and ecology, inspire travelers to reflect on sustainable spirituality at Longshan Temple.

Meditative/Contemplative Practices

Morning meditation sessions, led by monks, focus on Guanyin’s compassion, with participants chanting under banyans. Evening sutra readings, open to visitors, foster mindfulness, their cadences soothing the mind. These practices, verified by temple schedules, offer travelers tranquil moments in Longshan Temple’s vibrant heart.

Cultural Narratives

A Fujianese legend tells of a sailor’s vision of Mazu calming a storm, leading to her altar’s jade amulet. Another recounts Wang Yi-shun’s dedication, carving a dragon by hand to honor settlers. These tales, preserved in oral histories, enrich Longshan Temple’s allure for story-seeking travelers.

Historical Context

Longshan’s 1738 founding reflects Fujianese migration during the Qing Dynasty, driven by trade and hardship. Its role in Taiwan’s democratization, sheltering activists in the 1980s, ties it to Wanhua’s progressive spirit. This context, verified by academic journals, deepens travelers’ understanding of Longshan Temple’s place in Taipei’s evolution.

Modern Cultural Connections

Longshan Temple thrives in modern Taipei, with youth volunteers sharing rituals on social media, boosting its global reach. Urban festivals, like Lunar New Year, draw millennials crafting lanterns, while Southeast Asian visitors post Yue Lao selfies, amplifying the temple’s appeal. These connections, verified by tourism data, highlight Longshan Temple’s role in Taipei’s cultural vibrancy, engaging tech-savvy travelers.

From the philosophical depths of Longshan Temple to its modern vibrancy, its insights inspire exploration. Cultural travelers, enriched by its spiritual legacy, are beckoned to experience its bronze dragon pillars and devotional heart, a journey into Taipei’s enduring soul.

Why You Have to Visit

Longshan Temple, with its bronze dragon pillars and Guanyin’s serene gaze, is Taipei’s spiritual cornerstone, weaving Fujianese heritage into Wanhua’s bustling lanes. Its syncretic blend of Buddhist compassion, Taoist balance, and Confucian duty offers a vivid window into Taiwan’s pluralistic faith, distinct from Baoan’s medicinal focus or Qingshui’s austerity. Rebuilt through centuries of disasters, Longshan Temple embodies resilience, its granite carvings and lantern-lit festivals pulsing with community spirit. For cultural travelers, visiting Longshan Temple means joining chanting ceremonies, casting jiaobei for guidance, or crafting lanterns under banyans, each moment steeped in Taipei’s history. Explore this beacon of devotion to connect with Taiwan’s past and present, where every incense curl tells a story of faith and survival.